Overview

Over the holiday break, I received a few more random game platforms from friends and family who know how much I enjoy tearing into these things. While I didn’t find anything amazing or insightful, I did use some techniques and tools that I’ve not mentioned before here so I wanted to go over them in more detail. The purpose of this post is not necessarily about what lies within these ROM files, but more on the methods and tools used to extract the information.

Target 1: BasicFUN Oregon Trail

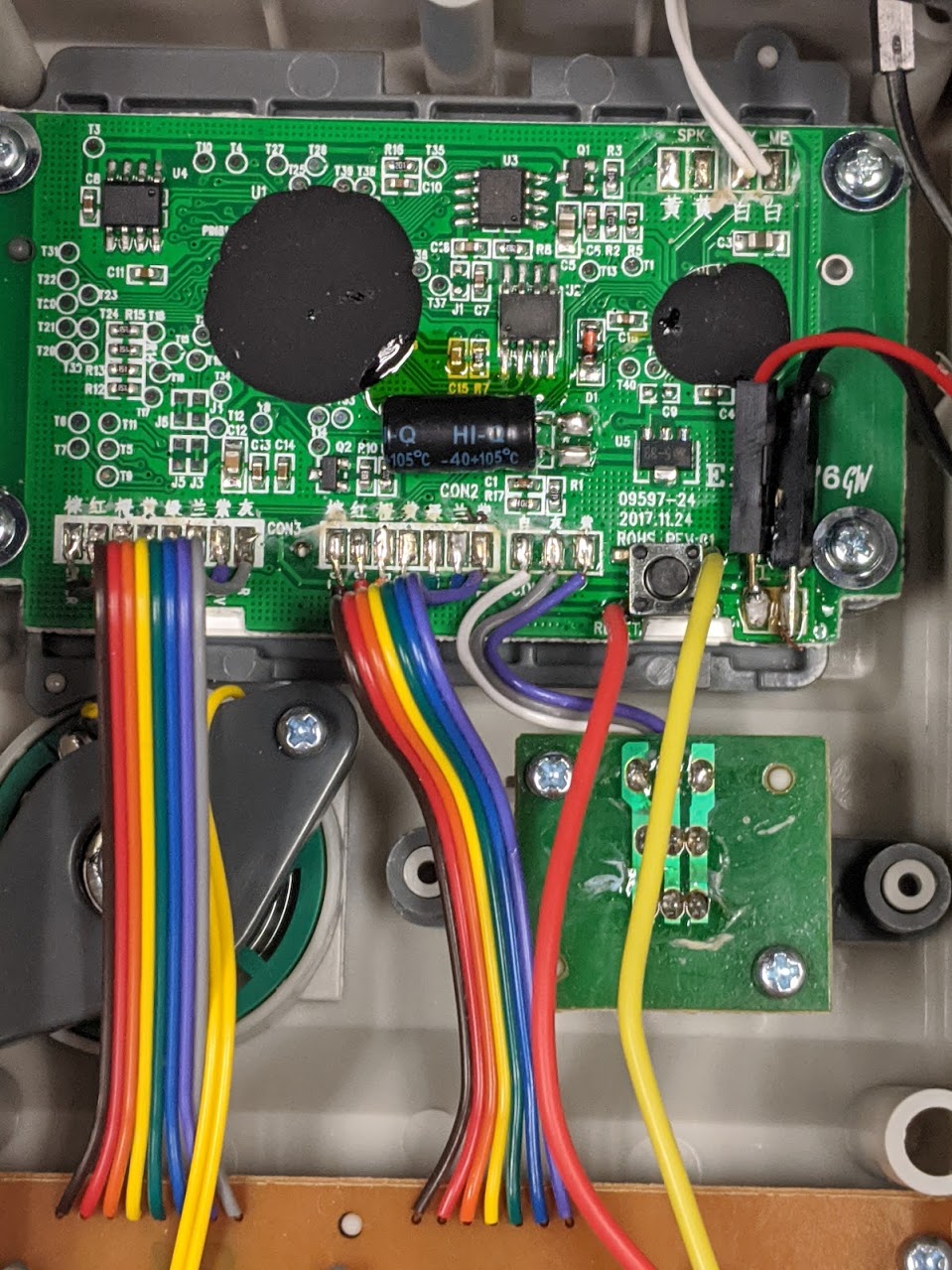

First and foremost, I should say that lots of people have taken this apart and even started to dig through the ROM, first who comes to mind is @foone on twitter, as well as Tom Nardi from hackaday. With that out of the way, lets take a look at the main board and see what we can identify.

Ok here we see the following part numbers on two TSOP8 chips that are placed in similar locations to the other platforms we’ve looked at in the past. Googling these part numbers results in the following

Excellent, one of these is a SPI flash which we have seen and dealt with before, while the other is an I2C based eeprom. We have covered how I2C works in previous posts but this will present us another opportunity to dig into this protocol with a different target.

Dumping the Flash with an FT2232

In the previous posts we used a buspirate to extract the flash, which is what I have traditionally used. After chatting with @securelyfitz on twitter, I decided to give the FT2232H breakout boards a try to see how well they work in comparison. We will still be using flashrom for the extraction but we’ll have to wire up the FT2232H accordingly.

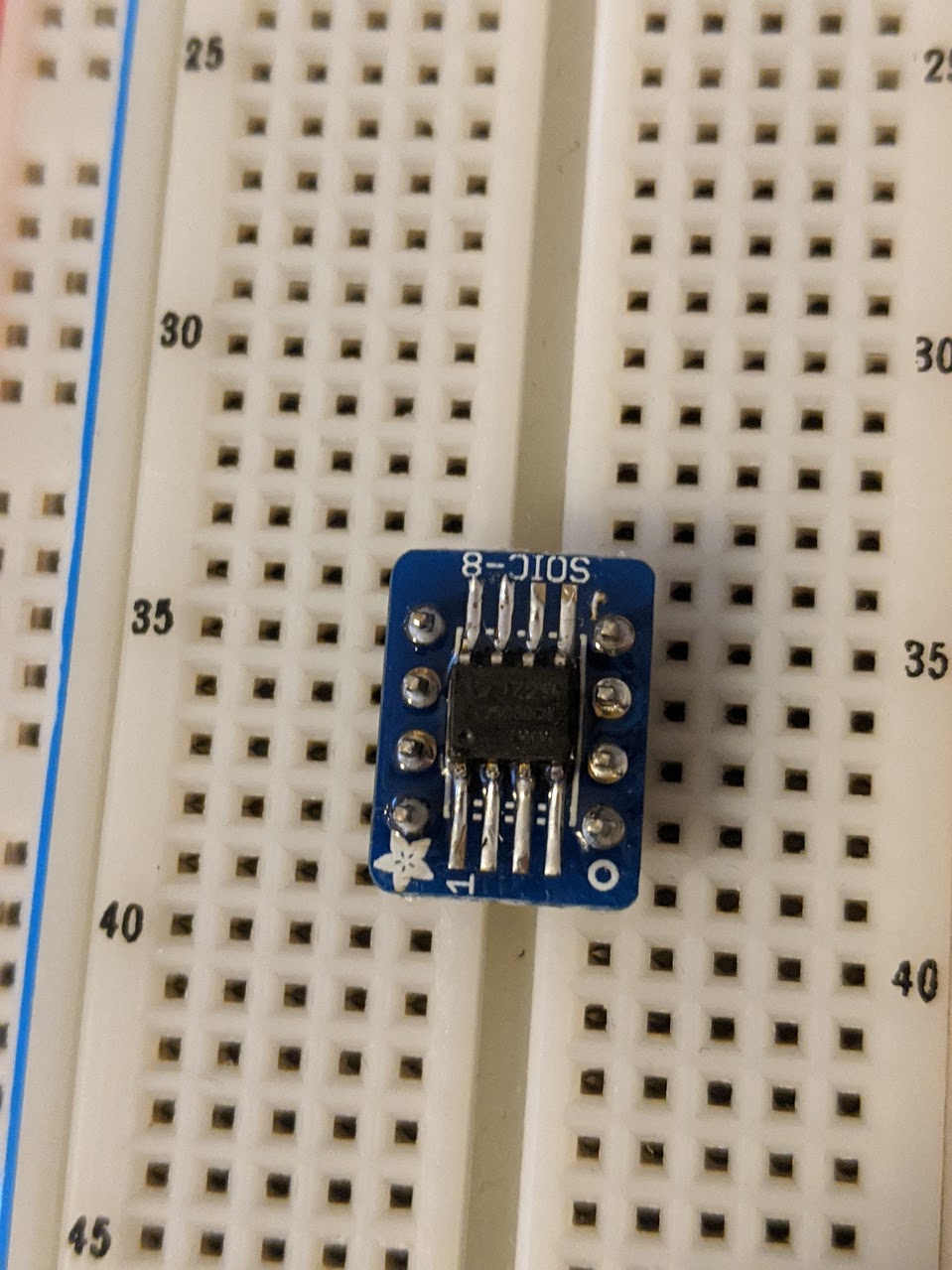

NOTE: Despite many attempts and multiple soldering jobs, I was not able to get consistent readouts working in-circuit, so for this platform we will be removing the SPI flash and placing it on a breakout board as seen below:

With the breakout board wired up, we connect the following pins from the SPI flash chip to the FT2232H board

| Flash Pin | FT2232H Pin |

|---|---|

CS | AD3 |

MOSI | AD1 |

MISO | AD2 |

CLK | AD0 |

With these wired up we will run flashrom as follows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

wrongbaud@wubuntu:~/blog/dec-teardown$ flashrom -p ft2232_spi:type=2232H -r oregon-trail-cab.bin

flashrom v1.1-rc1-125-g728062f on Linux 5.0.0-37-generic (x86_64)

flashrom is free software, get the source code at https://flashrom.org

Using clock_gettime for delay loops (clk_id: 1, resolution: 1ns).

Found GigaDevice flash chip "GD25Q80(B)" (1024 kB, SPI) on ft2232_spi.

Reading flash... done.

The first thing that I noticed is that this was noticeably faster than using the buspirate, this readout only took a matter of seconds.

It is important when extracting chips like this to always perform a few readouts to make sure that you’re getting consistent data.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

wrongbaud@wubuntu:~/blog/dec-teardown$ flashrom -p ft2232_spi:type=2232H -r oregon-trail-cab-2.bin

flashrom v1.1-rc1-125-g728062f on Linux 5.0.0-37-generic (x86_64)

flashrom is free software, get the source code at https://flashrom.org

Using clock_gettime for delay loops (clk_id: 1, resolution: 1ns).

Found GigaDevice flash chip "GD25Q80(B)" (1024 kB, SPI) on ft2232_spi.

Reading flash... done.

wrongbaud@wubuntu:~/blog/dec-teardown$ diff oregon-trail-cab.bin oregon-trail-cab-2.bin

Great, it looks like we’ve got a good firmware image of this platform. Digging through some of it in a hex editor, we see a reference to a possible debug mode, not unlike what we saw in other platforms

For the curious, the md5sum can be seen below:

1

2

wrongbaud@wubuntu:~/blog/dec-teardown$ md5sum oregon-trail-cab.bin

30729486a10915d9dd87b1e0d4c3e3b4 oregon-trail-cab.bin

Debug Mode

If you hold a certain button combination while powering up this platform, the following debug menu appears:

One of the interesting things on this menu is that there is the string 24C04…OK. What exactly is this doing? Presumably it is testing the I2C based EEPROM on the board, but what does this test look like?

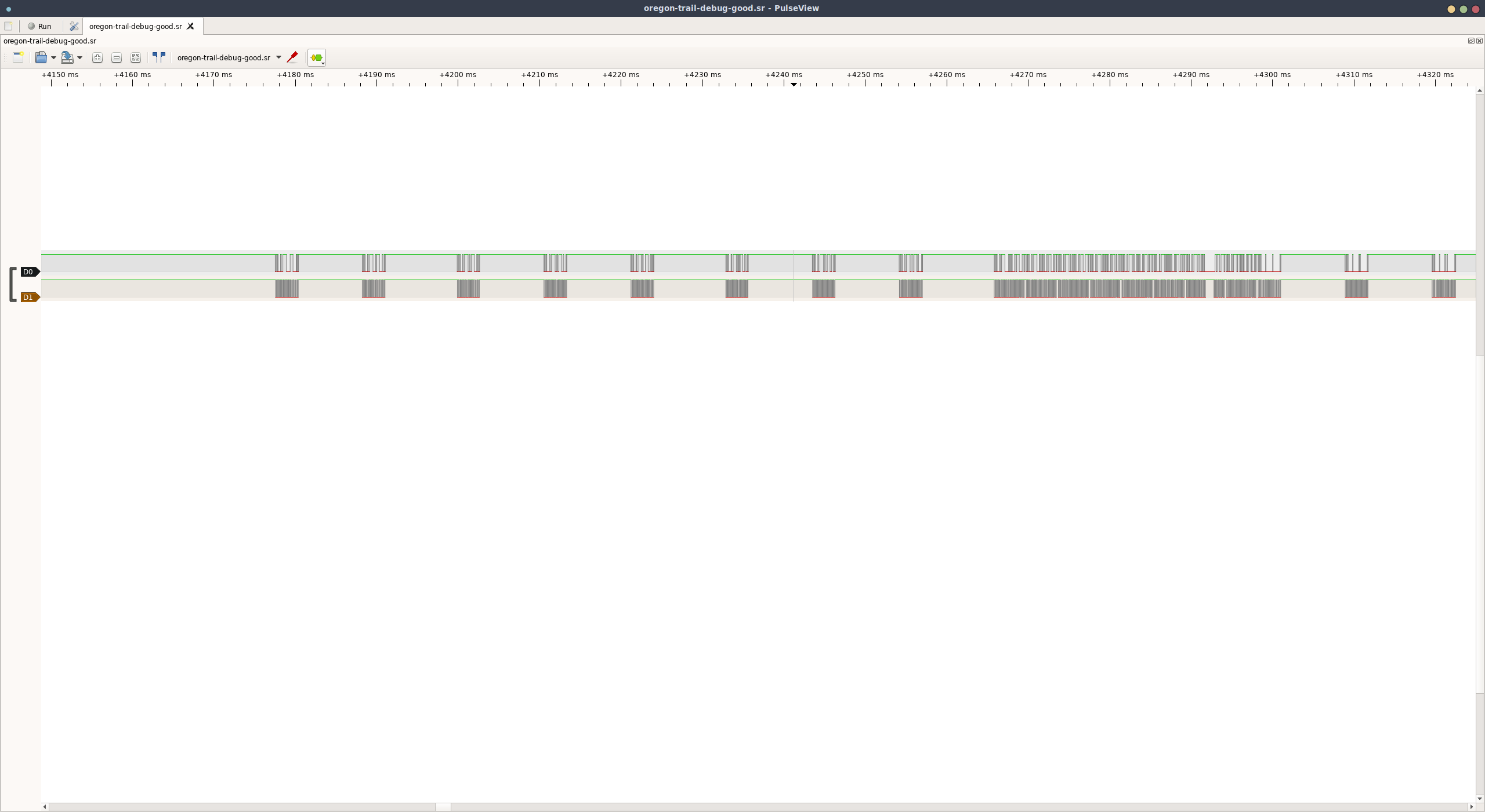

In order to introspect on what this test is actually doing, let’s hook up a cheap logic analyzer to the SDA/SCL pins of the EEPROM and enter the test mode again. Hopefully we will be able to see something come across the bus in Pulseview

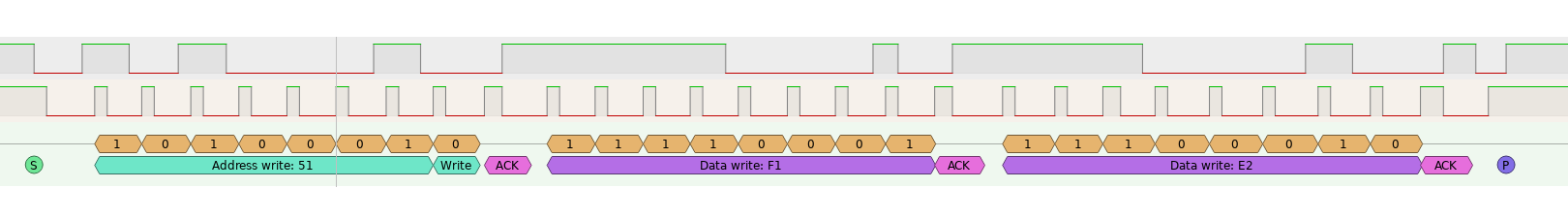

Sure enough, we see I2C traffic, but what exactly is it doing? If you need a primer on I2C, please see my previous post for some more information.

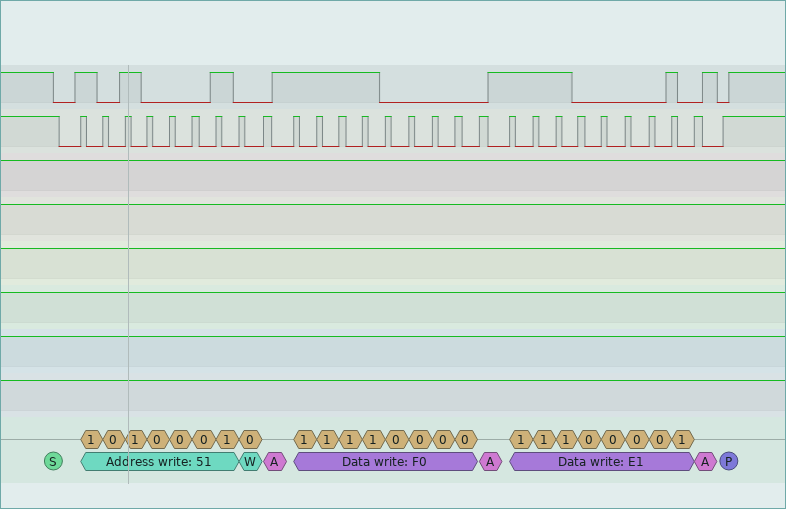

If we look at the first few packets, we see the following:

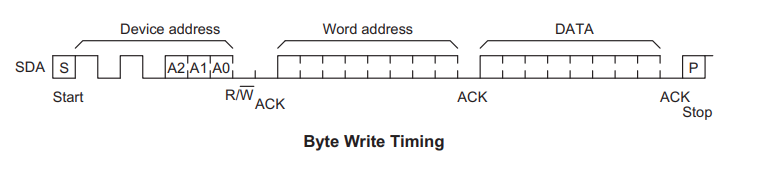

Ok so what exactly is happening here? First, 8 write operations are performs as shown in the images above. If we look at the datasheet, we can see that the following sequence outlines how to write to the flash device

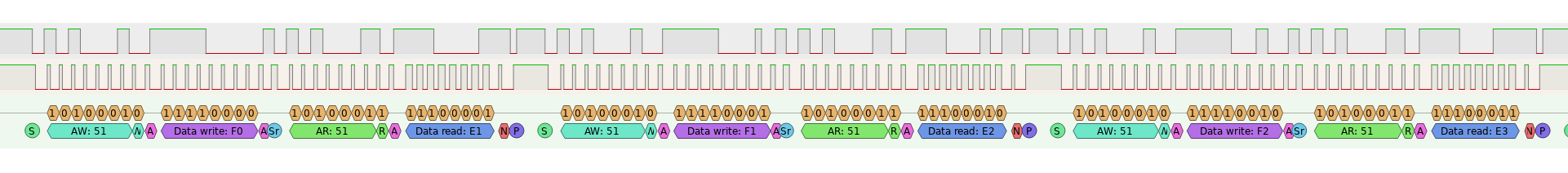

So the first 8 packets are writing bytes E1-E8 to addresses 0x1F0-0x1F7. Why 0x1F0 and not 0xF0? Well, the address bits A0:A1 for the I2C device are actually used to select the page that is currently being accessed, we will review this later on in the post when we dump the chip. After these writes are performed, the test simple reads them back out to check that the proper bytes were written which can be seen in the screenshot below. Neat!

Aside from this the debug menu has the standard tests for button presses and things like that. Moving on we’ll take a look at the contents of the I2C EEPROM and talk about how to extract these types of devices.

Exploring the I2C Flash

In the past, we’ve talked about communicating with I2C based peripherals, but this one will be a little different. Much like the other flash interfaces we’ve worked with there is a command that must be issued in order to perform a read operation. Luckily for us, i2cdump exists to handle this operation for us.

In order to utilize the i2cdump utility we will be using the BeagleBone Black, this a popular Linux based SBC that has many peripherals that come in handy when reverse engineering embedded systems. In our case we will be using the I2C2 channel, shown in the image below

We will be using pins 19/20 on the P9 connector in order to talk to this flash chip.

Connecting the I2C Flash to the BeagleBone Black

Looking at the datasheet, we can see that unlike the I2C chips we covered previously, A0 and A1 are used for page addressing with this eeprom, meaning that only A2 is used for the actual chip address. Essentially what this means is that performing a continual read operation at address 0x50 will perform a 2048 bit (0xFF byte) page read at offset ‘0’, while performing a read at 0x51 would perform the same function at the next page or, starting at offset 0xFF. The table below outlines how the I2C addresses map back to the offsets in the serial flash.

| I2C Address | Flash Address |

|---|---|

| 0x50 | 0x0 |

| 0x51 | 0x100 |

| 0x52 | 0x200 |

| 0x53 | 0x300 |

While A0:A1 are used for internal addressing of the flash pages, A2 is actually used for the I2C addressing of the chip itself, meaning that you can have up to 2 of these chips on the same I2C bus. For our purposes we will wire up the lines of the I2C flash as follows:

| I2C Flash | BeagleBone Black |

|---|---|

| A0:A2 | GND |

| VSS | GND |

| VCC | 3.3V |

| SDA | I2C_SDA (P9.20) |

| SCL | I2C_SCL (P9.19) |

So, now that we have the chip wired up to the BeagleBone, we can run the following commands to detect the I2C peripherals as well as any devices connected to those peripherals:

1

2

3

4

debian@sinistar:~$ i2cdetect -l

i2c-0 i2c OMAP I2C adapter I2C adapter

i2c-1 i2c OMAP I2C adapter I2C adapter

i2c-2 i2c OMAP I2C adapter I2C adapter

The i2cdetect will list the available I2C peripherals, on our case we’re using i2c-2 because those are the pins we connected to. Next we can probe for the actual flash device itself.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

debian@sinistar:~$ i2cdetect -r 2

WARNING! This program can confuse your I2C bus, cause data loss and worse!

I will probe file /dev/i2c-2 using read byte commands.

I will probe address range 0x03-0x77.

Continue? [Y/n] y

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f

00: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

10: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

20: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

30: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

40: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

50: 50 51 52 53 UU UU UU UU -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

60: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

70: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

Excellent! Here we can see that we have devices at 0x50:0x53 These essentially represent the 4 0xFF pages of the EEPROM. Now that we’ve confirmed we’re connected to the flash, we can use the i2cdump command to see the contents. Below is a very simple series of commands that will display the information contained within the flash.

1

2

3

4

5

6

debian@sinistar:~$ cat i2c.sh

i2cdetect -r 2

i2cdump -y 2 0x50

i2cdump -y 2 0x51

i2cdump -y 2 0x52

i2cdump -y 2 0x53

Running this we see the following output:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

debian@sinistar:~$ ./i2c.sh

WARNING! This program can confuse your I2C bus, cause data loss and worse!

I will probe file /dev/i2c-2 using read byte commands.

I will probe address range 0x03-0x77.

Continue? [Y/n] y

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f

00: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

10: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

20: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

30: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

40: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

50: 50 51 52 53 UU UU UU UU -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

60: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

70: -- -- -- -- -- -- -- --

No size specified (using byte-data access)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f 0123456789abcdef

00: aa 53 74 65 70 68 65 6e 20 4d 20 20 20 20 20 20 ?Stephen M

10: 20 44 61 76 69 64 20 48 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 David H

20: 20 41 6e 64 72 65 77 20 53 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 Andrew S

30: 20 43 65 6c 69 6e 64 61 20 48 20 20 20 20 20 20 Celinda H

40: 20 45 7a 72 61 20 4d 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 Ezra M

50: 20 57 69 6c 6c 69 61 6d 20 56 20 20 20 20 20 20 William V

60: 20 4d 61 72 79 20 42 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 Mary B

70: 20 57 69 6c 6c 69 61 6d 20 57 20 20 20 20 20 20 William W

80: 20 43 68 61 72 6c 65 73 20 48 20 20 20 20 20 20 Charles H

90: 20 45 6c 69 6a 61 68 20 57 20 20 20 20 20 20 20 Elijah W

a0: 20 e2 1d 3e 16 2a 10 81 0b 04 08 79 05 a9 03 67 ??>?*?????y???g

b0: 02 8c 01 fa 00 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ????.???........

c0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

d0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

e0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

f0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

No size specified (using byte-data access)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f 0123456789abcdef

00: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

10: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

20: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

30: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

40: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

50: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

60: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

70: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

80: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

90: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

a0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

b0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

c0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

d0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

e0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 ................

f0: 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 aa 55 ..............?U

No size specified (using byte-data access)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f 0123456789abcdef

00: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

10: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

20: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

30: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

40: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

50: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

60: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

70: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

80: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

90: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

a0: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

b0: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

c0: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

d0: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

e0: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

f0: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

No size specified (using byte-data access)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 a b c d e f 0123456789abcdef

00: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

10: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

20: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

30: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

40: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

50: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

60: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

70: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

80: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

90: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

a0: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

b0: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

c0: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

d0: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

e0: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

f0: ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ff ................

So with the BeagleBone, we’re now able to properly read out the contents of the I2C flash, it looks as this contains save game state, as well as 2 unused pages. So at this point, we’ve properly dumped out all of the storage mediums on the Oregon Trail handheld, and shown how to use some different tools along the way!

Target 2: ATGames Blast

Second on the list, is a simple HDMI based game device that was given to me by a friend who knows how much I enjoy tearing these things apart. They were kind enough to give me two (they were on sale at target for $5 apparently) knowing that one would likely be torn apart.

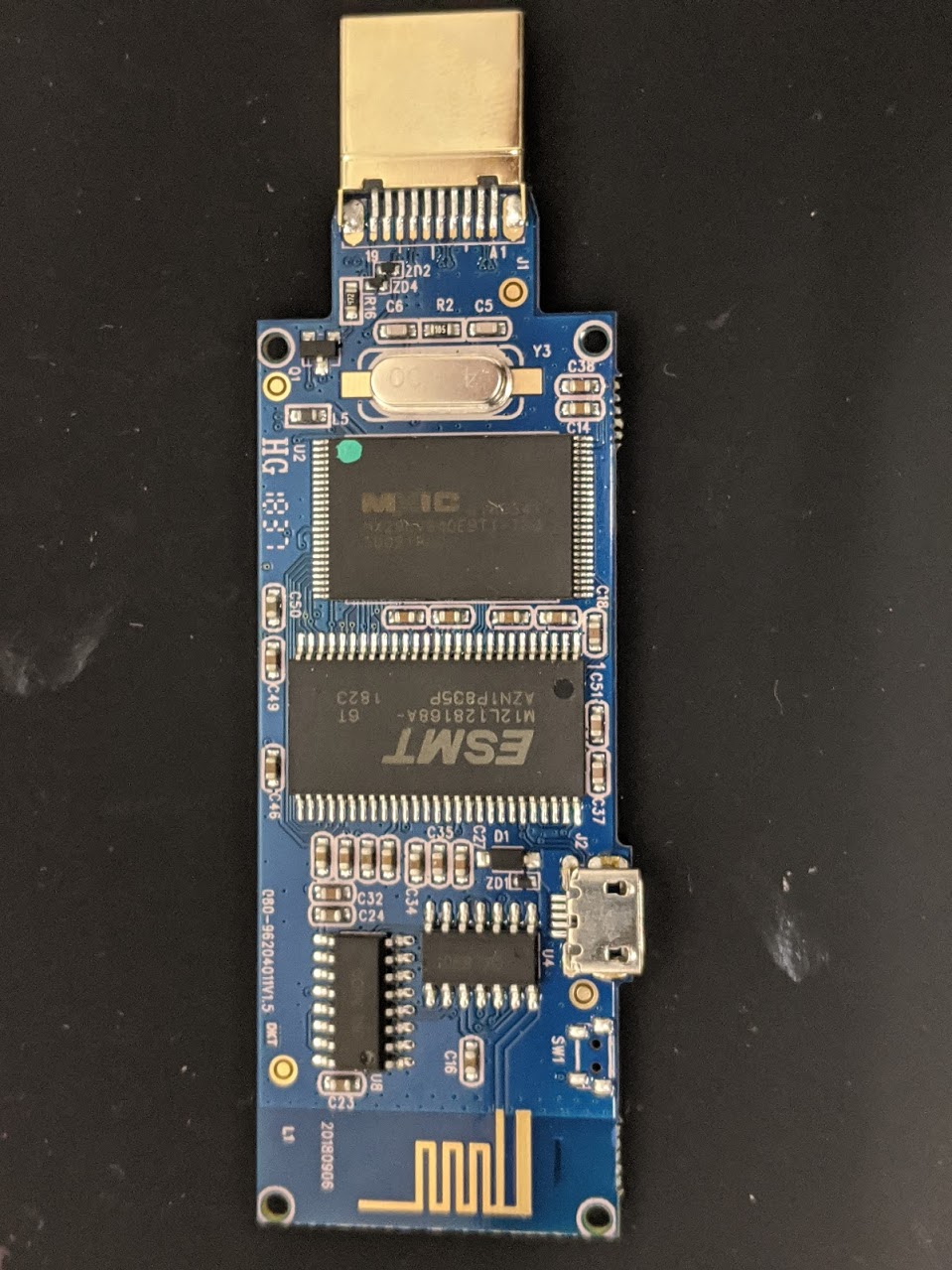

Hardware Overview

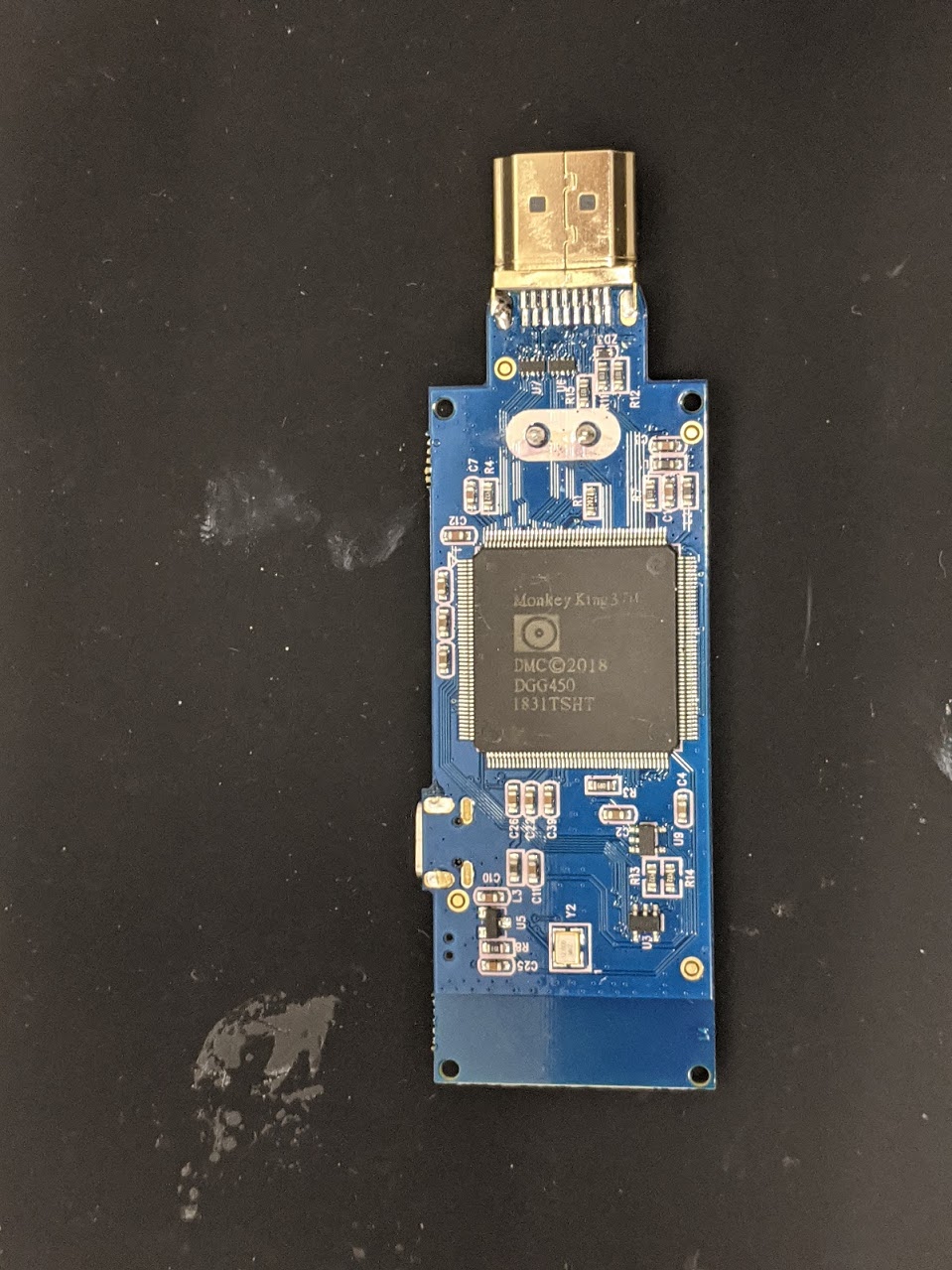

Taking a look at the main PCB, there isn’t much here. On one side we can see the main processor (MonkeyKing), on the other we’ve got an SRAM chip (ESMT chip) and a Parallel flash. There is also an antenna on one end of the PCB and a USB connector for power. Nothing terribly surprising here.

Let’s take a look at the contents of this flash chip using flashtality

Extracting and exploring the flash with Flashtality

Using the tooling that we previously put together for the Mortal Kombat cabinets, we can remove and attempt to dump this chip.

1

python scripts/dump.py -i 192.168.1.186 -p 3333 -a 0 --size 800000 --ofile atgames-full.bin

If we take a look at the firmware with binwalk we see the following:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

wrongbaud@wubuntu:~/blog/flashtality$ binwalk atgames-full.bin

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

346837 0x54AD5 Certificate in DER format (x509 v3), header length: 4, sequence length: 5376

377207 0x5C177 Copyright string: "Copyright 1995-2004 Mark Adler "

377676 0x5C34C CRC32 polynomial table, little endian

381772 0x5D34C CRC32 polynomial table, big endian

385883 0x5E35B Copyright string: "Copyright 1995-2004 Jean-loup Gailly "

459264 0x70200 gzip compressed data, has original file name: "menu", from NTFS filesystem (NT), last modified: 2018-08-16 09:43:46

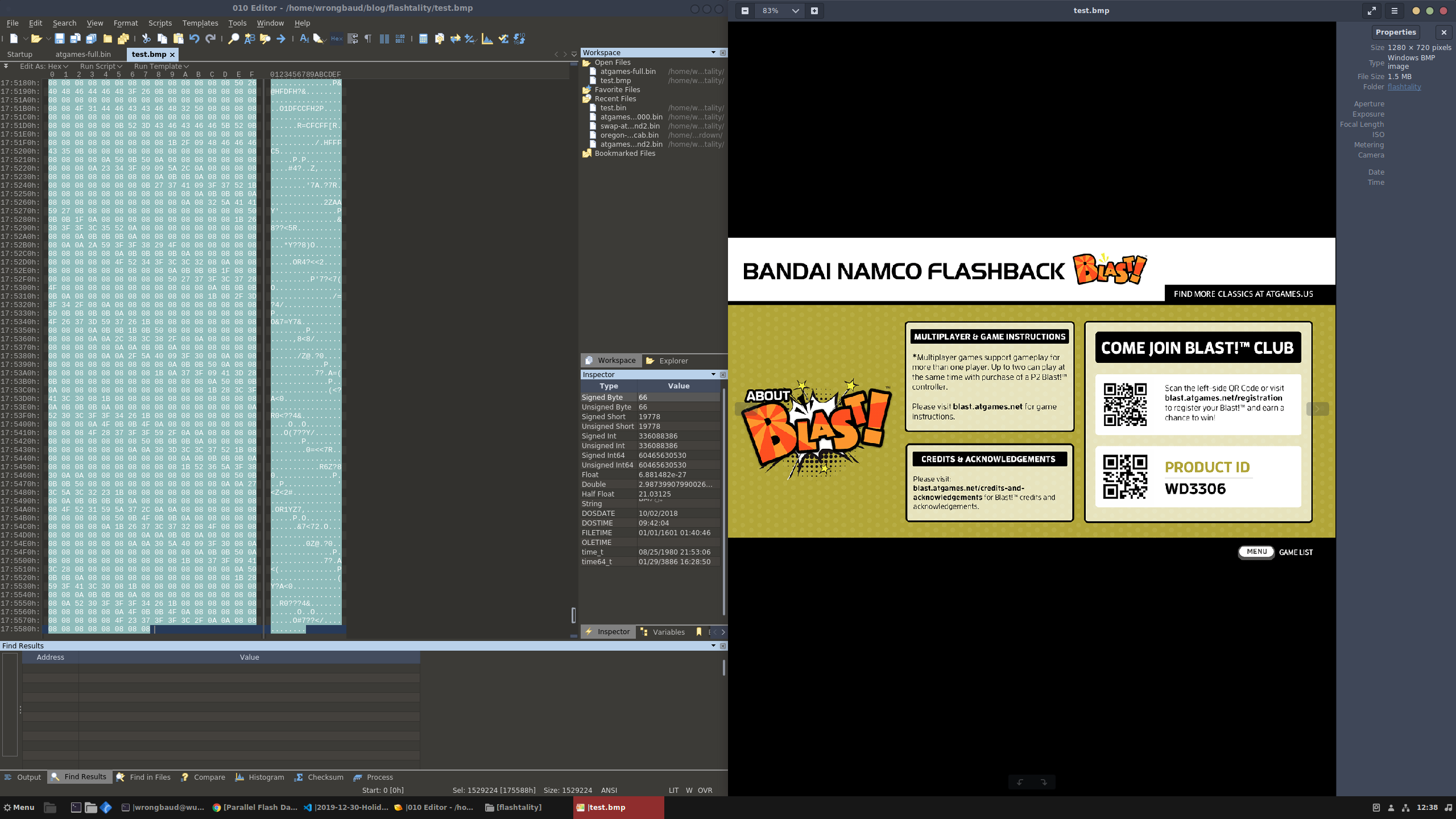

606592 0x94180 PC bitmap, Windows 3.x format,, 1280 x 720 x 8

1529224 0x175588 gzip compressed data, has original file name: "DigDug.nes", from NTFS filesystem (NT), last modified: 2018-07-20 17:56:54

1544276 0x179054 gzip compressed data, has original file name: "Galaga.nes", from NTFS filesystem (NT), last modified: 2018-07-16 21:58:36

1560973 0x17D18D gzip compressed data, has original file name: "Galaxian.nes", from NTFS filesystem (NT), last modified: 2018-07-16 22:19:14

1571200 0x17F980 gzip compressed data, has original file name: "Mappy.nes", from NTFS filesystem (NT), last modified: 2003-01-19 06:10:48

4396647 0x431667 gzip compressed data, has original file name: "Pacman.nes", from NTFS filesystem (NT), last modified: 2018-07-17 11:11:52

4407779 0x4341E3 gzip compressed data, has original file name: "SkyKid.nes", from NTFS filesystem (NT), last modified: 2018-07-17 11:41:34

4440177 0x43C071 gzip compressed data, has original file name: "TowerOfDruaga.nes", from NTFS filesystem (NT), last modified: 2018-07-17 11:48:14

4463879 0x441D07 gzip compressed data, has original file name: "Xevious.nes", from NTFS filesystem (NT), last modified: 2018-07-16 22:27:58

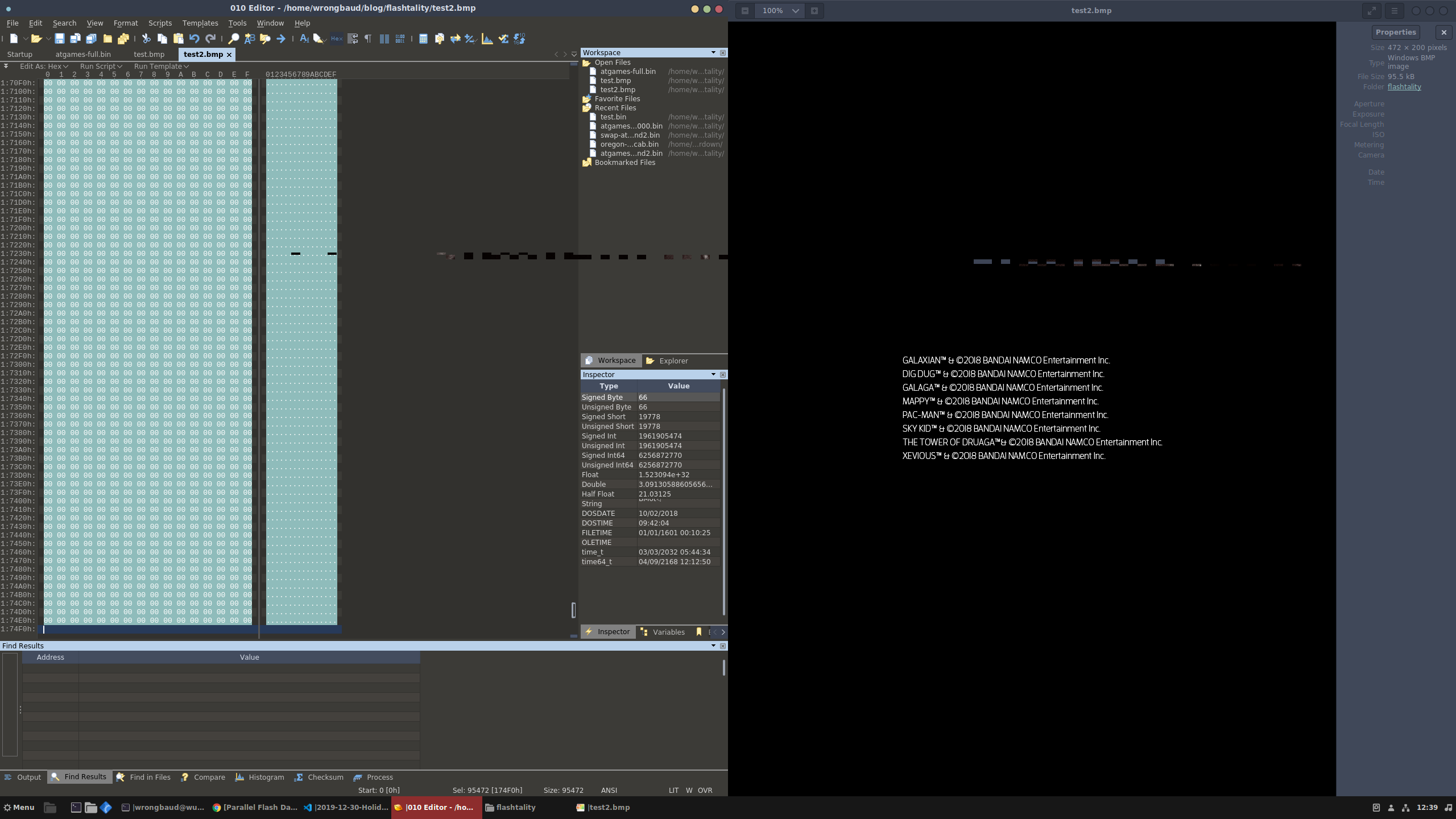

4487983 0x447B2F PC bitmap, Windows 3.x format,, 472 x 200 x 8

4583455 0x45F01F gzip compressed data, has original file name: "ines", from NTFS filesystem (NT), last modified: 2018-08-16 09:43:44

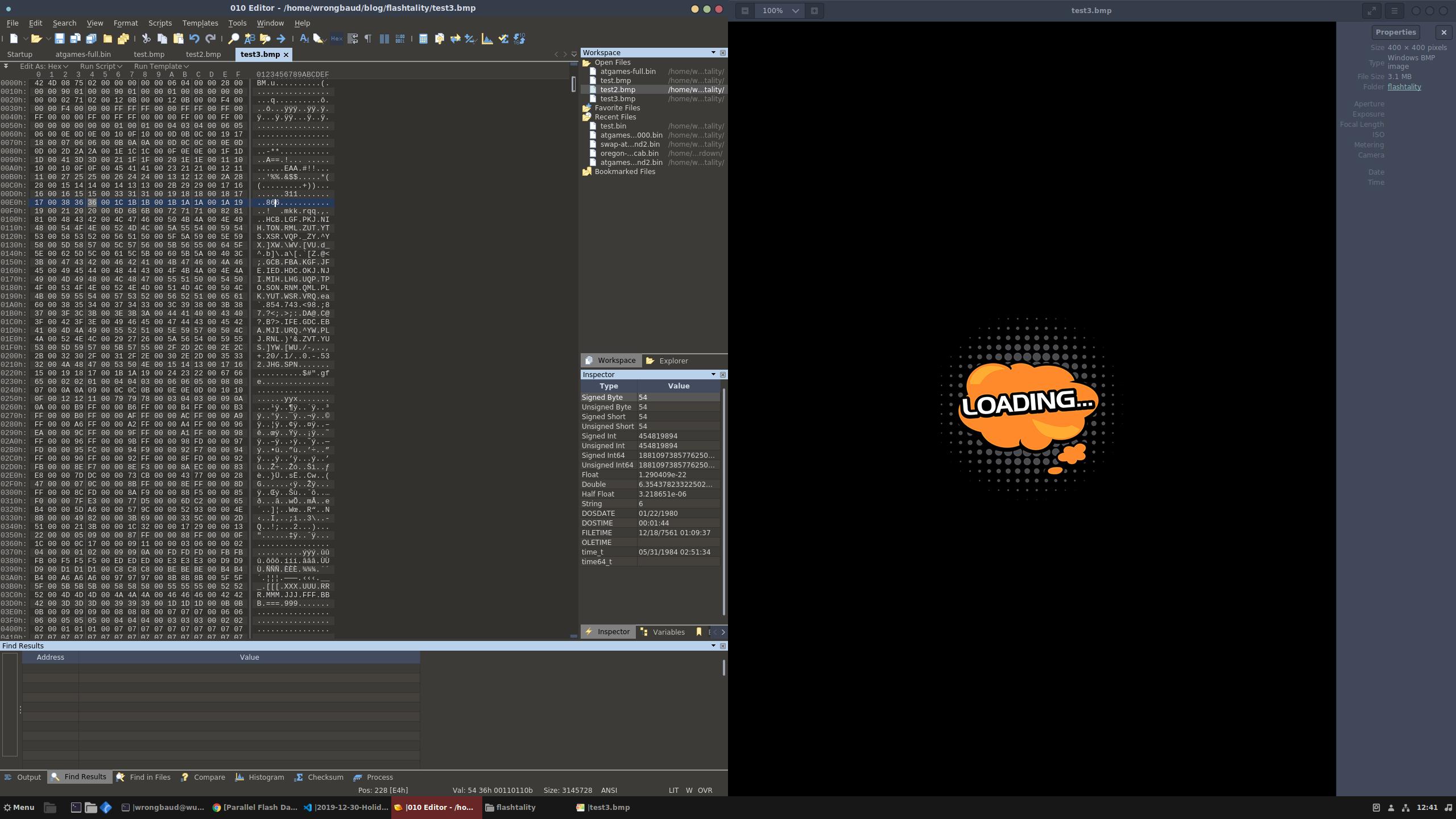

4797314 0x493382 PC bitmap, Windows 3.x format,, 400 x 400 x 8

Luckily this flash dump was fairly straightforward and binwalk was able to find a lot of things! Let’s start by pulling out the bitmaps, and see what those look like.

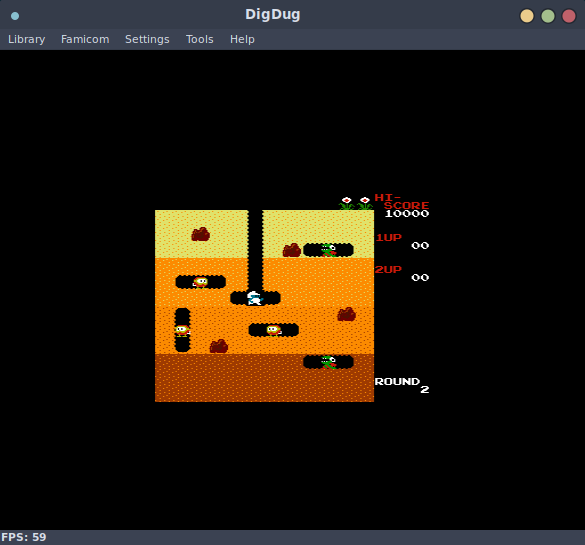

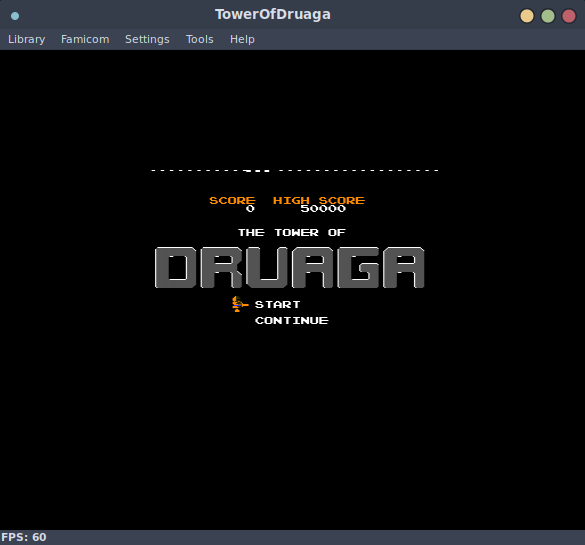

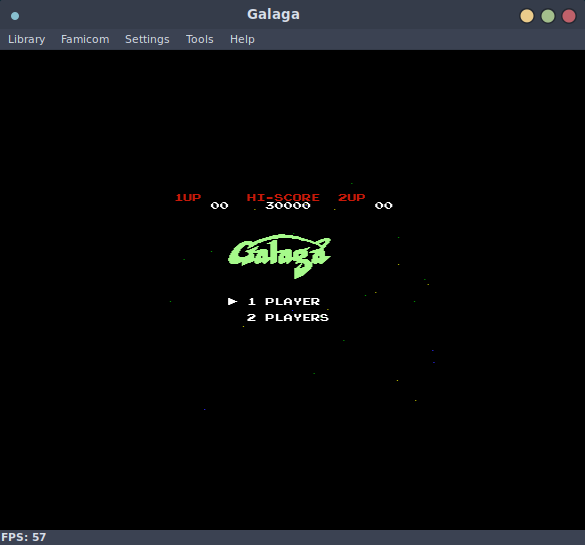

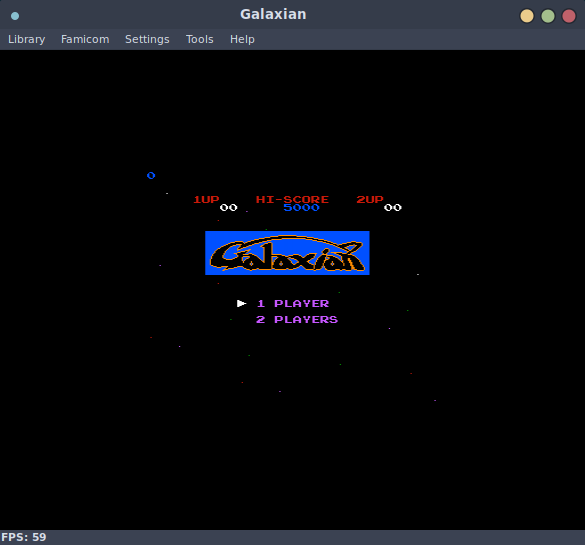

Alright, this all looks good, these are some of the splash screens and loading screens. Next on the list are the NES roms that are embedded in the flash image, let’s pull those out and see if they run in emulators:

1

binwalk -e atgames-full.bin

Using the -e flash with binwalk will cause binwalk to attempt to auto-extract files that are found in the target. The resulting files from this can be seen below.

1

2

3

wrongbaud@wubuntu:~/blog/flashtality/_atgames-full.bin.extracted$ ls

DigDug.nes Galaga.nes Galaxian.nes ines Mappy.nes menu Pacman.nes SkyKid.nes TowerOfDruaga.nes Xevious.nes

So it looks like we’ve got two binaries in here that are not nes ROMs. This makes sense as this CPU is some sort of low cost ARM CPU. Menu is likely what you interact with and see when you turn the game on, and if I had to guess I would say that ines is the NES emulator that runs. Let’s try to run each .nes file in higan

1

2

3

4

wrongbaud@wubuntu:~/blog/flashtality/_atgames-full.bin.extracted$ for file in $(ls *.nes)

> do

> higan $file

> done

Nice! All of these run in an emulator, this is really neat for a handful of reasons, but mainly that if one were so inclined, you could reflash this firmware image with new NES roms and play them! Perhaps I will take a look at this once I implement write support in flashtality.

Conclusion

I wanted to get one last post out the door for 2019, if there are things or topics that you would like to learn more about or see featured, please reach out to me on twitter and let me know. With this write up, we took a look at two new platforms, extracted all of the information from each and learned about interfacing with I2C EEPROMs. We used a BeagleBone Black to communicate with an I2C EEPROM as well as an FT2232H to extract a SPI EEPROM via flashrom. Lastly we utilized the ESP32 based flashtality tool in order to extract information from a new platform. Hopefully this information was of interest and can serve as a reference for those doing similar work. Thanks for taking the time to read, and please reach out with any feedback or questions

Blog Updates (as of 2022):

Future blog posts and entries can be found here.

If you are interested in learning more about reverse engineering check out my 5 day hardware hacking course, public and private offerings are available upon request

Never want to miss an update or blog post? Check out my mailing list for a quarterly newsletter about reverse engineering embedded devices